An explanation of how the smuggling was done

1784 Act of Parliament – Preventing “Hovering”

A page from an 1784 Act of Parliament explains that any vessel found at anchor less than 4 leagues (about 14 miles) from the coast, without reporting to a Customs officer, was deemed to be “hovering.”

The penalties were severe: fines of up to £200 and the confiscation of cargo or the ship.

To combat this, the South West Coast Path was later developed. It allowed HM Customs officers, known as “Riders,” to spot suspicious vessels and prevent crews from recovering hidden contraband underwater using a method called “creeping.”

How did the Pengersick Smugglers locate smuggling ships?

Watching the Bay: Pengersick Castle and Smuggling at Sea

Pengersick Castle was the only true lookout point in the area and, although already in ruins during the Carter brothers’ time, it remained high enough to command clear views across Mounts Bay. From the tower, smugglers could easily see vessels arriving offshore and monitor the Shoals of Cudden or the Welloe's, shallow stone reef and sandbanks ideal for hiding contraband beneath the water.

Cargo had to be landed—or hidden—quickly. Under the Loitering or “Hovering” Law of 1784, any vessel lingering near the coast risked a £200 fine, confiscation of ship and cargo, and in some cases pursuit by revenue cutters. Capture could mean imprisonment—or worse.

To avoid this, ships would drop their cargo overboard in the shoals, marking the spot using transit points—alignments of landmarks shown on Admiralty charts of the time. Once the larger vessel had slipped away and “the coast was clear” (a phrase born from this very practice), smaller boats or gigs would return under cover of darkness. Using grappling hooks, the smugglers would recover the sunken barrels in a process known as “creeping.”

These techniques allowed smugglers to outwit Customs officers and exploit the landscape and seascape to their advantage—turning ruins, shoals, and darkness into powerful allies.

Smugglers, Shoals and the Tides of Prussia Cove

Pause at a high point overlooking the bay, the shoals, and the cove.

“Imagine it’s the 1700s. Darkness falls, and the only light along this coast comes from candles, torches, and oil lamps. This was the world of the Carter brothers — men who quite literally owned the night.

From this vantage point, the smugglers would first spot the target: a vessel approaching the Cornish coast, heavy with cargo that ordinary people desperately needed — salt to preserve pilchards, tea, spirits, and everyday goods taxed beyond reach.

But spotting a ship was only the beginning. As the old saying went, ‘a smuggler must know the tides — and know when to seize them.’

The entire operation depended on timing. The wrong tide could strand a boat, expose a landing, or leave men trapped under the guns of the Revenue. The right tide, taken at exactly the right moment, could make a cargo vanish without trace.

Using old Admiralty charts, the Carters chose precise transit points — shallow areas where a ship could hover just long enough to work. Here, depths of around 2 to 4.5 metres allowed a strong swimmer to descend a shot line, untie the barrels of contraband, and bring them to the surface. Everywhere else the sea floor dropped away too steeply.

These transit points line up almost exactly with Pengersick Castle Tower, which, though in ruins at the time, remained the highest and most strategic lookout. From there, the smugglers could see the bay, the shoals, and any Revenue cutters approaching long before they were in danger.

On the chart you’ll notice:

- Red areas, marking the Admiralty gun batteries — places to avoid at all costs.

- Green areas, the safe water — where a smuggler’s gig could slip in quietly and land its cargo, either at the foot of the hill below Smugglers Barn, or further along toward what later became John Carter’s own gun battery at Prussia Cove, these area's were out of the prying eyes of the Revenue & Customs.

Everything had to be done quickly. The Hovering Act of 1784 meant that lingering offshore with cargo could bring ruin — fines of £200, confiscation of ship, or worse. So barrels were sometimes sunk deliberately in the shoals, to be recovered later by grappling hook in a process known as ‘creeping’ — once again, only possible if you knew the tides intimately.

After years of mastering this coast, John Carter married Joan Richards in 1765 and, by 1770, built a house at Prussia Cove, recognising how perfectly the landscape, tides, and shelter worked together. From here he could oversee landings, watch the sea lanes, and move unseen.

Harry Carter, after a lifetime of privateering, imprisonment, and daring escapes, eventually retired to Rinsey Head, where he purchased a farm — a rare ending for a smuggler who survived the gallows, the sea, and the law.

As you stand here today, with the waves rolling in below, imagine the quiet precision of those nights — the waiting, the watching, the tide turning — and the moment when everything aligned. Because along this coast, timing was everything, and those who seized the tide survived.”

See the chart below, we have zoomed in on the Shoals of Cuddan to see the exact depth and Mountamopus as it is called is only 5 to 6 Metres deep. (16 to 18 feet)

Here is a zoomed in shot of the Stone, it is as shallow as 3 Metres (9 foot) and a very large area to drop barrels ready for “Creeping”. Which we will explain what "Creeping" is soon.

How did they recover the Cargo unseen?

Guided Walk: Smugglers’ Signals and the Art of Creeping

“Take a look at the photo below. This is how a smuggling operation began: with signals. The Carters and other smugglers had a whole language of secret communications.

From the ship, they could shine a signal lamp, emitting a thin, precise beam of light to the shore.

On land, the lookout would watch for flags flown in specific ways, or notice window patterns — curtains opened or closed in a particular sequence during the day, lights on in certain rooms at night, or even washing hung in a special colour on a particular day. Each sign had a prearranged meaning: ‘The coast is clear.’

Once the message was received, the ship would carefully ‘hover’ over the shallow transit points — the shoals of Cuddan or the Stone — without landing, while barrels of contraband were lowered onto the sea bed. The shore team then went ‘creeping’: moving silently along the beach and wading into the shallow water to recover the cargo, making sure no customs officers saw a thing.

It was a delicate operation that relied on timing, secrecy, and absolute knowledge of the tides and sea conditions. One wrong move, and the cargo could be seized — or worse, fines or imprisonment could follow under the strict Hovering Law of 1784.

This was smuggling at its most ingenious: a combination of observation, coded signals, and careful coordinationbetween ship and shore — all done in the dark, under the watchful eye of the coast.”

the signal lamp

the signal lamp

Signals, Secrecy, and the Smuggling Act

“As smuggling became more organised, Parliament responded with ever harsher laws. One of the most feared was the Smuggling Act, which didn’t just target ships at sea, but the people on shore as well.

Under this law, anyone caught using lights, fires, flashes, or signals to communicate with a vessel offshore could face severe punishment. Even standing on the coast and helping to signal a ship was a crime. The penalty was staggering for ordinary people: a fine of £100, or up to a year of hard labour in prison.

And there was a further twist. To encourage betrayal, the authorities offered rewards of up to £25 to anyone who informed on their neighbours. In tight-knit Cornish communities, this was meant to sow fear and mistrust.

Yet despite the risks, when a ship heavy with contraband arrived in the bay, the response could be extraordinary. Up to a hundred local people might gather on the beach to help unload. Men, women, and children formed silent human chains, moving barrels inland before the Revenue riders could arrive.

Why take such risks? Because for many families this was not crime—it was survival. Smuggled tea, salt, and spirits were often the difference between hunger and food on the table.

So when you stand here today, looking out across the bay, remember: every light mattered, every signal was dangerous, and every successful landing was an act of quiet defiance against laws made far away, by people who would never face the hardships of coastal Cornwall.”

Creeping

the signal lamp

A Smuggler’s Night: From Signal to Shore

“Now imagine this place at night.

No streetlights. No engines. Just wind, tide, and darkness.

High above us, in the ruins of Pengersick Castle, a lookout waits. He knows the sea as well as the land. He knows the tides, the shoals, and—most importantly—when to seize them. A smuggler who misjudges the tide risks losing everything: cargo, ship, or life.

Out in the bay, a ship appears. She does not come close. She hovers—six miles offshore if the weather allows—just far enough to stay beyond the law. Her captain lines her up using transit points, one of them the ruined tower behind you. When the landmarks align, he knows he is above the shoals of Cuddan or the Welloe.

A signal is exchanged.

A thin blade of light cuts briefly through the darkness from shore. Perhaps a shuttered lamp. Perhaps a flag by day, washing hung in a certain way, or a window left deliberately lit. The message is simple and deadly dangerous:

The coast is clear.

The ship moves quickly now. Barrels are rolled overboard, tied, and dropped into the shallow water. They sink, but not too far—just deep enough to hide, shallow enough to recover. If the Revenue appears, the ship can flee at once, leaving nothing but empty sea behind her.

Now comes the most dangerous part.

From the shore, a gig slips silently into the water. Oars are muffled. Voices are forbidden. The men know the depth by memory. They reach the spot and begin creeping.

A grappling hook is lowered. Sometimes it finds a barrel. Sometimes it doesn’t. If it fails, a man slides into the black water, following a shot line straight down. He unties the rope, signals once, and the barrel rises from the seabed like a ghost.

One by one, the cargo is hauled aboard.

All the while, eyes are on the land. The law is never far away. Under the Hovering Acts, fines of £200, prison, transportation—or death—await anyone caught loitering or signalling. Informers are paid. Neighbours can betray neighbours.

Yet still they come.

On a good night, a hundred local people may be waiting on the beach: fishermen, miners, farmers, women and children too. Silent chains form. Barrels move inland, vanish into lanes, barns, and hidden cellars.

By dawn, the bay is empty again.

No ship. No cargo. No proof.

Only the knowledge that once more, the smugglers have beaten the law—not for greed alone, but because in places like this, smuggling meant survival.

And that is why these cliffs, these shoals, and this ruined tower mattered. The sea was their ally. The night was their cover.

And for a few hours at least…

They owned it.

the owlers on shore

John Carter and the Poem That Made Him Immortal

John Carter’s reputation spread far beyond Prussia Cove. His smuggling exploits became part of coastal legend—so much so that they helped inspire Rudyard Kipling.

In 1906, Kipling published “A Smuggler’s Song”, capturing the unspoken rules that governed places like this: silence, loyalty, and trust. The poem remains famous today, and its most chilling line sums up the smuggler’s code perfectly:

“Watch the wall, my darling, while the gentlemen go by.”

These were not gentlemen in fine coats—but men moving through the night with contraband and courage, bound by a shared understanding that some things were better not seen.

Kipling’s verses echo exactly what happened here:

If you wake at midnight, and hear a horse’s feet,

Don’t go drawing back the blind, or looking in the street.

Them that ask no questions isn’t told a lie—

Watch the wall, my darling, while the gentlemen go by.

Five and twenty ponies trotting through the dark—

Brandy for the Parson, ’baccy for the Clerk.

Laces for a lady; letters for a spy—

Watch the wall, my darling, while the gentlemen go by.

This was the world John Carter lived in—a world where silence was currency, loyalty was law, and the night belonged to those who understood it.

👉 Please click the link below to hear the full poem, “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pELNBp6DBh8

And as you stand here now, listening to the sea, it’s not hard to imagine it again:

the creak of oars, the weight of barrels, the whisper of boots on shingle—

—and the Owlers, ready and waiting, watching the wall.

the tub man

The Night’s Quiet Work

Once the gigs had been unloaded by the Owlers and the tubs hauled clear of the tide, the task of the tub-man began. The tub-man was usually a strong farm labourer, accustomed to carrying heavy loads, who bore the tubs inland from the beach.

He carried them steadily and without haste, often along narrow lanes or tracks known only to the smugglers.

Rather than being taken to houses or farm buildings, the tubs were commonly carried to concealed tunnel entrances or underground passages. These tunnels, cut into cliffs, hillsides, or leading inland from the shore, provided a secure place to hide contraband until it could be moved on or quietly distributed.

By daylight, the beach and surrounding land would show little sign of the night’s work. The contraband — spirits, tobacco, and other illicit goods — lay hidden below ground, beyond the immediate reach of the excise officers, while the tub-man returned to his ordinary labour as though nothing had occurred.

Why did locals help the smugglers?

Smuggling at Praa Sands: A Coast Built for the Trade

Between 1760 and 1810, smuggling became an established and organised way of life along the coast at Pengersick. Britain was engaged in a succession of expensive wars, and the cost was met through heavy taxation. Imported goods were particularly targeted, with steep duties placed on items such as wine, spirits, tobacco, tea, and salt, often inflating their prices many times over.

Life for ordinary people in the Praa Sands area was already harsh. Those not working in the local tin and copper mines, labouring six and a half days a week by candlelight underground, depended on the sea for their living. Fishing and the preparation of pilchards and sardines for export were vital industries, and fine salt was essential for preserving the catch destined for Mediterranean markets. Yet even this necessary commodity was heavily taxed.

Smuggling filled the gap left by these burdens. Local families relied on affordable salt, while the middle and upper classes depended on smugglers for reasonably priced tea, brandy, tobacco, lace, and spirits. What the authorities regarded as criminal activity was, to many in Praa Sands, a practical response to unfair taxation and economic necessity.

Praa Sands was particularly well suited to smuggling. Its broad beach and nearby coves allowed cargo to be landed quickly, while its position on the south coast placed it within a day’s sail of Jersey, Guernsey, and the Breton coast of France.

Longstanding maritime connections, shared trading routes, and similarities between the Breton and Cornish languages helped sustain these links.

Equally important were the skills of the local population. Praa Sands and the surrounding area were home to experienced fishermen, capable sailors, and highly skilled miners, whose knowledge of underground workings was put to use in the creation and adaptation of tunnels used to hide and move contraband. Supported by the local community, these advantages made Pengersick one of Cornwall’s most effective smuggling locations during the late eighteenth century.

who would buy their contraband? and who is "cousin Jack"

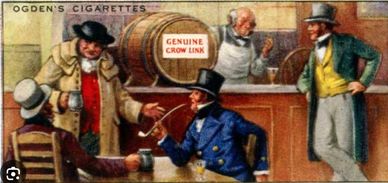

Winks, Winks Back: Smuggling and the Public Houses & "Cousin Jack"

The Carter family sold their goods to people from all walks of life — from ordinary working families to the gentry, and even members of the judiciary. Their trade was so widespread and discreetly accepted that it was later said no court in Cornwall would convict them, as too many stood to benefit.

Public houses played a central role in the smuggling network and often served as trading points known as “winks.” These inns were places where information, goods, and signals could be exchanged in plain sight, unnoticed by outsiders.

A short walk west from Praa Sands along the coastal path — about two and a half miles — brings you to Bessie’s Cove, now known as Pisky’s Cove. Here stood a well-known wink, the Kiddlerwink, run by Bessie Bussow. Like many such establishments, the pub kept one barrel on display for the customs officers. This was the legal barrel, from which drinks were sold at a much higher price.

Those in the know could ask instead for a glass of “Cousin Jack.” The term referred to Cornish miners who travelled the world for work — it was said that everyone had a Cousin Jack somewhere — and in this context it signalled a barrel that had arrived through smuggling channels. Ordering “Cousin Jack” meant a drink from under the counter, or sometimes from a kettle kept out of sight.

A wink exchanged between customer and landlord was all that was needed. If the wink was returned, it meant contraband was available. Smugglers themselves would also wink to signal that brandy or other goods had arrived and were ready for sale. In this way, trade continued quietly and efficiently, hidden behind everyday social life in the inns along the Praa Sands coast.

And here is a good example of a "Wink Pub"

Located in Lamorna Cove

how remote was pengersick in carter's reign ?

A Remote Stronghold: Pengersick and the Smuggling Coast

Above is an 18th-century hand-coloured engraving showing the east view of Pengersick Castle, produced around 1740 by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck as part of their survey of English castles. The engraving is valuable not only as an image of the castle itself, but also for what it reveals about the extreme remoteness of the surrounding landscape at the time.

To understand the position of Smugglers’ Barn, begin by facing the tall oval doorway of the castle as it stands today. From there, walk down the drive to the road, just as shown in the engraving. Looking slightly to the left, the barn stands directly ahead. Its two-storey form is clearly visible in the engraving, and no other dwellings appear nearby. This absence of buildings confirms how isolated Pengersick was in the eighteenth century.

That isolation is vividly described in the Autobiography of Captain Harry Carter, whose account provides an invaluable contemporary insight into the area. Carter describes a stretch of coastline between Marazion and Helston, broken by Cuddan Point, where the character of the land changes dramatically. West of the point, Mount’s Bay was sheltered and increasingly populated. To the east, however, the coast became wild and exposed, marked by steep cliffs and long beaches such as Praa Sands, where Atlantic seas made landing dangerous except on rare calm days.

With the exception of Porthleven, Carter notes that there were no settlements large enough to be called villages along this coast. Inland, the landscape was bare and windswept, divided by stone hedges and scattered with small hamlets of only a few cottages each — including Pengersick, which lay close to what is now Prussia Cove.

At the time Carter was writing, the district was described as almost inaccessible. Roads were few or non-existent, travel was largely by bridle path, and packhorses were still in common use. Contemporary accounts confirm that West Cornwall in the mid-eighteenth century was sparsely developed and difficult to police. This remoteness, combined with a deeply skilled local population of sailors, fishermen, and miners, made the area ideally suited to smuggling.

Carter’s autobiography remains one of the most authentic records of the smuggling trade in Cornwall. Official correspondence from the 1750s confirms his account, describing coastlines that “swarmed with smugglers” and calling for troops to be stationed nearby. Against this backdrop, places such as Pengersick, isolated yet well connected by sea and underground routes, played a significant role in the organisation and concealment of contraband along the Praa Sands coast.

Source:

The Autobiography of a Cornish Smuggler — Captain Harry Carter of Prussia Cove (1749–1809), first published 1809; second edition introduction by John B. Cornish, 1900.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.