Pengersick is marked on many world ancient maritime maps dating right back to 1630

%20-54b78e9.jpg/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:1240,cg:true)

painting by William Payne, 1826 of Pengersick Castle

A Place Steeped in History

Smugglers Barn sits at the heart of the historic hamlet of Pengersick, a place where documented history and local legend intertwine.

An 1826 watercolour by William Payne (1750–1830) shows Pengersick Castle in ruins to the right, and — on the far left — two small cottages standing on the land where Smugglers Barn now stands. The painting captures the hamlet during the period of John Carter’s ownership, when the castle had already fallen into decay.

This image provides rare visual evidence that buildings have occupied the site of Smugglers Barn for over two centuries.

If you stand facing Smugglers Barn today, where the Blue Plaque is located, Pengersick Castle rises directly behind you. Historical records from the early 19th century describe the castle at that time as little more than a romantic ruin — impressive, atmospheric, and already rich in story.

Smugglers and the Black Dog of Pengersick

Pengersick is long associated with smuggling folklore. The most famous legend is that of the Black Dog of Pengersick, said to roam the ruins with glowing eyes.

In reality, historians now believe this story was invented by 19th-century smugglers to discourage local people from approaching the area. Fear was a useful tool.

From the top of the castle’s ruined tower, smugglers could see far out into the bay, watching for ships arriving with contraband — and just as importantly, for Revenue Cutters patrolling the coast. It is from this practice that the phrase “the coast is clear” is thought to originate.

Hidden Tunnels and Watchful Eyes

Behind the castle tower lay a hidden stash tunnel, running beneath bog land near the footpath leading to Trevurvas. Local accounts suggest the tunnel eventually led to the beach, providing a discreet escape route.

A local farmer recalls that in the 1970s a cow fell into part of the tunnel and had to be rescued by the fire brigade. The tunnel was later adapted for drainage and boarded up for safety.

From their vantage point on the tower, smugglers would have been able to see anyone approaching both the tunnel and the buildings below — including the area now occupied by Smugglers Barn.

Legend and Reality

Over the years, stories of ghosts, devil worship, and dark rituals have surrounded Pengersick Castle. Modern research has shown many of these tales to be exaggerated or entirely false — but they remain part of the castle’s enduring mystique.

Today, visitors can enjoy Pengersick not just for its legends, but as a fascinating glimpse into Cornwall’s smuggling past and the long history of this remarkable landscape.

Where were the Carter Brothers Born?

Cornwall’s Most Famous Smugglers — John & Harry Carter

Many historical records show that John Carter and Harry (Henry) Carter, two of Cornwall’s most famous smugglers, were born in the hamlet of Pengersick — the same small community where Smugglers Barn now stands.

The Carter Brothers

The Carter family were among the best-known smugglers in late 18th-century Cornwall. They operated out of Prussia Cove, a series of secluded inlets on Mount’s Bay, using the rugged coastline and hidden coves to land and move contraband goods along the Cornish coast.

John Carter (born 1738) was given the nickname the “King of Prussia”, reportedly because he admired Frederick the Great and was known locally by this name throughout his life. He became a central organiser of the family’s smuggling operations, respected locally for his fair dealings even as he defied customs authorities.

Harry Carter (born 1749 in Pengersick) was the fourth of the seven Carter brothers. His own autobiography — first published in the Methodist Journal and later widely reproduced — tells how he began smuggling in his late teens, captained several vessels, endured imprisonment, and eventually became a Methodist preacher after leaving smuggling behind.

Smuggling, Privateering, and Local Life

The Carter brothers' activities blended smuggling and privateering; they obtained letters of marque (licenses for armed ships) during times of war and were involved in maritime adventures as well as illicit trade.

Their exploits were rooted in local geography and economy. Cornwall’s remote coves, wooded footpaths, and marshy coastline offered secluded routes for moving cargoes away from the watchful eyes of revenue officers — and created legends that now form part of Cornwall’s rich heritage.

Harry Carter's autobiography above tells of his father Francis being a "hard labouring man", who brought up his children in “decent poverty” and that Harry was born on a little farm in Pengersick. His autobiography was first published in 1809. It is quite easy to confirm that John and Henry Carter were born in Pengersick. Please search for them on google by simply putting in “Carter family born in Pengersick”. This is easy enough but please read further and find out exactly where and how as smugglers they stashed their booty?

“The Story of an Ancient Parish Breage with Germoe” By H R Coulthard Published 1913

Life in Pengersick: Hardship and Faith

Contemporary records from the period describe “the problem of daily bread in the household”, highlighting the severe hardship faced by much of the Cornish population at the time. Food poverty was widespread, and survival often depended on smallholdings, faith, and community support.

The accompanying illustration reinforces this reality and confirms that Harry Carter was born on a small farm in Pengersick. It also records that Harry was able to read the Bible — an important detail, as literacy was far from universal among the rural poor.

Harry later became a Methodist, attending Germoe Church, the nearest church to Pengersick. Germoe would have been the spiritual centre for local families, linking the hamlet to wider religious and social life in the area.

The book from which this information is drawn has been made publicly available by Germoe Parish Council, allowing visitors and researchers alike to learn more about the history, hardship, and beliefs of people living in and around Pengersick during this period.

- Page 129 CHAPTER VIII - WORTHIES AND UNWORTHIES

Harry Carter: Childhood, Hardship, and Faith

The book (Shown above) Story of an Ancient Parish: Breage with Germoe records that Harry Carter — later known as a smuggler, privateer, and religious revivalist — was born in 1749 on a small farm at Pengersick.

His father was a miner who supplemented the family’s income by farming a small plot of land, with help from his children. Harry later wrote in his memoirs that he was one of ten children — eight sons and two daughters. Only the eldest and youngest received a small amount of formal schooling at Germoe School. For Harry and the rest of the family, education went little further than basic reading, taught at home through the Bible.

The book describes “the problem of daily bread in the household”, reflecting the severe poverty faced by many Cornish families at the time. From an early age, the children were expected to work — in the fields or the mines — so that each could contribute to the family’s survival.

Despite these hardships, religious life played an important role in the household. The children were taught prayers, often recited at bedtime, and attended services at Germoe Church when possible — the nearest church to Pengersick and the centre of local worship.

Harry’s childhood coincided with a period of religious revival in Cornwall, influenced by the preaching journeys of John Wesley. These early experiences would later shape Harry Carter’s dramatic transformation from smuggler to Methodist preacher.

Smuggling in Devon & Cornwall 1700-1850 by mary waugh

IT STATES BELOW HARRY'S FATHER RENTED

IT STATES BELOW HARRY'S FATHER RENTED

IT STATES BELOW HARRY'S FATHER RENTED

a smallholding in Pengersick.

IT STATES BELOW HARRY'S FATHER RENTED

IT STATES BELOW HARRY'S FATHER RENTED

Pengersick and Smugglers Barn: A Historic Overview

As you can see on the map below, Pengersick is a tiny hamlet. The location of Smugglers Barn is marked with a red arrow — the only building shown with an attached plot of land. This plot would have been a smallholding, consistent with historical accounts of the Carter family living here in the 18th century. While the map itself dates over 100 years after the Carters’ time, it helps illustrate the small scale of the settlement and the rural character that has long defined Pengersick.

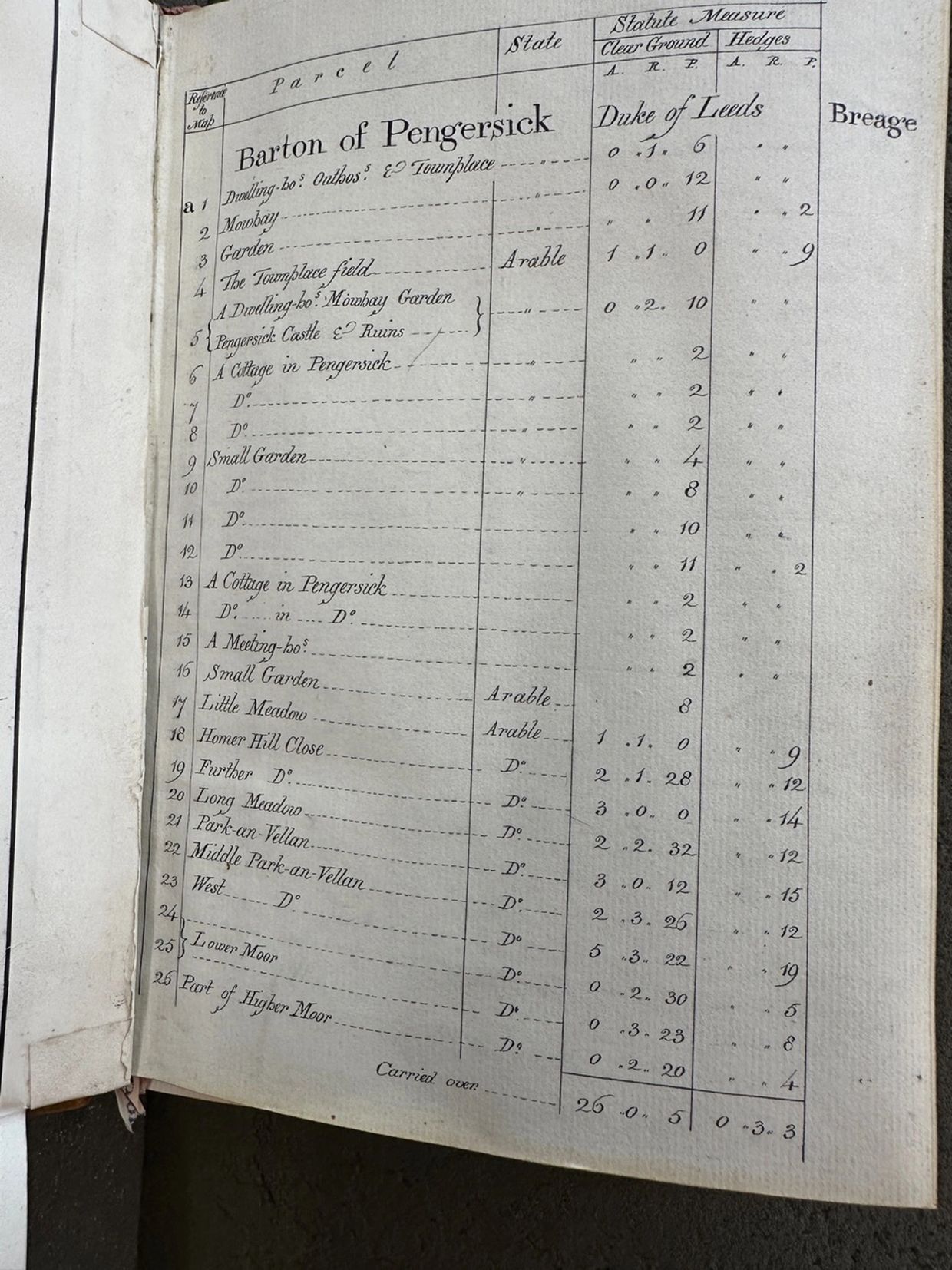

By kind permission of Kresen Kernow, Cornwall’s main history archive, the photograph below shows a historic map from the 1830s that accompanies the rent book for the Barton of Pengersick and the State of Trevurvas. In the 1830s, a “barton” referred to a farm or agricultural estate, often linked to a manor house or grange. On this map, Pengersick Castle sits at the centre, Which at the time of the Carter family's time at the smallholding was in ruins, with surrounding properties and fields numbered to match entries in the rent book.

Together, these maps provide a rare glimpse into the organisation of land in Pengersick — showing smallholdings, farms, and the castle estate — and help visitors understand the historic setting of Smugglers Barn, once part of the hamlet’s agricultural landscape.

ordnance survey map of Pengersick 1888-1913

Above a photograph of a lease of properties in Pengersick Rented from Lord Godolphin Ist June 1832

Above lease of properties in Pengersick rented from Lord Godolphin - Ist June 1832

Understanding the Map Scale: Chains and Acres

If you look closely at the historic map, you’ll notice the scale is measured in “chains”.

A chain was the standard tool surveyors used to measure land — a long, linked metal chain that made it easier to measure uneven fields and hilly terrain. Each chain measured 66 feet (about 20 meters).

The acre, another historic unit on the map, was originally defined as the amount of land a team of oxen could plough in a single day. Together, these measurements helped surveyors accurately map estates, farms, and smallholdings like those in Pengersick.

This means when you look at the map showing Smugglers Barn and the surrounding fields, the scale gives a real sense of the size and layout of the land as it would have been in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Take a look at 13a, 14a & 15a plus the fields 16a & 17a

The Carter Family Smallholding in Pengersick

We have found multiple historical sources confirming that John and Harry Carter, Cornwall’s most famous smugglers, were born on a smallholding in Pengersick. Some books refer to it as a farm, but all agree it was a modest agricultural plot.

If you compare the photo below with the Barton of Pengersick map from 1830, you can see the main barn and the Methodist chapel clearly marked. According to the rent book and map, there were no other dwellings or buildings for rent in this immediate area — the next available properties were in neighbouring hamlets such as Trevurvas Wollas, Trevurvas Wartha, or Higher Pengersick. This highlights the Carters’ home as a true smallholding at the heart of Pengersick.

Land Measurements: Acres, Roods & Perches

The historic rent book uses the statute measure of ARP: Acres, Roods & Perches.

- 1 Rood = ¼ acre (Source: Nottingham University)

- For example, the Meadow (plot 17) is recorded as 1¼ acres.

According to Harry Carter’s autobiography, the Carter family paid 12 Libra per year (Latin for pound, equivalent to £12 today) for the smallholding. The rent book we reference is from 1832, which gives a good indication of the likely rent for a typical Pengersick smallholding at that time.

This information, combined with the map, photo, and rent records, helps paint a vivid picture of the Carters’ humble beginnings in Pengersick, showing the scale of the land and the simple life that shaped Cornwall’s most famous smugglers.

Rent and Value of the Carter Family Smallholding

Historical records show that in 1840, the fair average rent for land in Cornwall was 25 shillings per year, equivalent to £1.25 in decimal currency.

The Carter family, however, paid £12 per year for their smallholding — nearly ten times the average rent. This suggests that the property was more than just a single plot: it likely included the two cottages, the Methodist meeting house facing east, and the land behind the dwellings.

This aligns with what we know from maps and rent books: the Carter family’s smallholding in Pengersick was modest, yet significant enough to support a large family, and it formed the foundation of the home of Cornwall’s most famous smugglers, John and Harry Carter.

Read more here about land use in Cornwall in the 18th Century.

Above please see at 13a, 14a & 15a plus the fields 16a & 17a

Take a look at the scale in the map and it's measured in Chains. This was literally how a surveyor measured a field, with a big long chain it was easier to measure because the land went up and down, and the acre started out as a standard unit of land area, historically defined as the area a team of oxen could plow in a day.

The Castle footprint (above) and Pengersick (today)

Smugglers Barn and Pengersick Castle

- Smugglers Barn (formerly Pengersick Barn) is a Grade II listed property.

- The barn sits outside the original castle footprint. The fortified manor house, or castle, is nearby, but Smugglers Barn is on its own plot, as confirmed by aerial views and Historic England maps.

- The castle courtyard outline can still be seen today from the position of the remaining buildings and the dividing road.

Buildings Opposite Smugglers Barn

- Across the stream from Smugglers Barn, the old buildings are marked on various historical maps.

- At the time of the Carters’ reign, these buildings were already in ruins.

- They are marked with a red arrow in the National Trust photograph below.

Date: 1850–1875

Source: National Trust

https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1520795

the castle buildings opposite still in ruins

Pengersick today

Here is the building today our property called “Smugglers Barn” which is a grade II listed property. The aerial view shows that the barn is not on the footprint of the Tower which stands on the site of Pengersick castle and if you look at the old maps and Listed buildings in Pengersick, Smugglers Barn is the only one outside the Tower ‘castle’ footprint as also confirmed from the Historic England Castle Footprint Map below. From the aerial view you can see the outline of the original castle courtyard by the position of the buildings and the road dividing it.

The wesleyan chapel attached to the smallholding

Harry Carter the Methodist

Looking at Smugglers Barn (marked with the green arrow in the photo above) on Cornwall Council’s interactive map, we can see its historical context:

- The two adjacent cottages would have originally been built in line with the cart track leading between the castle. These are the same cottages mentioned in the rent book.

- At the end of the row, the building angled slightly differently is the Chapel or “Meeting House”, oriented exactly east to west, typical of Methodist meeting houses and churches. This building would have been constructed after John Wesley first came to Cornwall in 1743, who visited the region over 30 times, with his final visit in 1789.

- Looking closely at Smugglers Barn, the two left-hand windows have very thick lintels, suggesting that the barn was once attached to a much taller building, likely part of the chapel complex.

Historical postcards from the 1930s confirm that there were no other dwellings in the area, reinforcing that Smugglers Barn, the cottages, and the chapel were the only main structures in Pengersick at the time.

Harry Carter’s Methodist Faith

From Harry Carter’s autobiography, A Cornish Smuggler (1749–1809):

“No Swearing. I allwayse had a dislike to swearing, and made a law on board, if any of the sailors should swear, was poneshed. Nevertheless my intention was not pure; I had sume byends in it, the bottom of it was only pride… I wanted to be noted to be sumething out of the common way of others, still I allwayse had a dislike to hear others swearing. Well, then, I think I was counted what the world cales a good sort of man, good humoured, not proude.”

We also know that John Carter, Harry’s brother, was a Methodist preacher. According to The Story of an Ancient Parish: Breage with Germoe (H. R. Coulthard, 1913):

“His youth coincided with the strange stirrings in the religious life of the people brought about by the not infrequent peregrinations of John Wesley through the district. When Harry was eight years of age the soul of his brother Francis was touched.”

It is likely that Harry observed the poverty and struggles of ordinary Cornish people, who were deprived of basic necessities while distant decisions in London affected hardworking fishermen, miners, and farmers. and what better place to meet with the local population to exchange money and goods but the local Chapel.

The Farmstead at Pengersick

- On the historic map of Pengersick, the Meeting House (building 15) lies east to west, consistent with Methodist practices.

- There are no other properties on the Pengersick map with enough land for a smallholding or farm.

- The road separates the cottages and chapel from the castle, explaining why historical sources describe Harry and John Carter as being “born on a farm in Pengersick” rather than at Pengersick Castle itself.

where did the preaching take place?

If you look closer into the large photo above at the end of the meeting house you can see someone in a black robe, similar to the one in the small photo of the gown above.

This would be the sort of attire a methodist preacher would wear at that time.

- Smugglers Barn (green arrow) shows thick lintels, indicating the building was taller than the adjacent cottages. This suggests it was the second cottage on the plot.

- The Chapel (or “Meeting House”) is visible on the left of the photo.

- It is detached from the cottages.

- Its alignment is slightly different from the cottages, running exactly East–West, as was typical for Methodist churches and meeting houses.

This separation between the cottages, the Chapel, and the Castle footprint shows why historical records describe Harry and John Carter as being born on a smallholding in Pengersick, not in Pengersick Castle itself.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.